Family Office

Credit Lines, War Chests And Liquidity: How Family Offices Are Positioning – Deutsche Bank Study

A study from the German bank into the investment habits of family offices worldwide delves into attitudes about borrowing money to finance investment, how they amass resources to exploit long-term asset shifts, and their approach to liquidity.

Family offices are increasingly becoming more institutional in how they invest, use leverage and are building “war chests” to capture opportunities when asset prices fall, a new study from Deutsche Bank says.

Illiquid assets form a core part of portfolios, are being leveraged more often, while most family offices engage in private credit and expect high returns, the Family Office Financing Report 2025, based on views of 209 family offices globally, has found. Survey work was conducted between 9 May and 14 July. The 44-page study said around 35 per cent of respondents were responsible for portfolios with more than $1 billion, and a further 27 per cent sat in the $250 million to $1 billion range.

The study kicked off by examining how family offices use credit and lending facilities – an obvious point for Germany’s largest bank to raise.

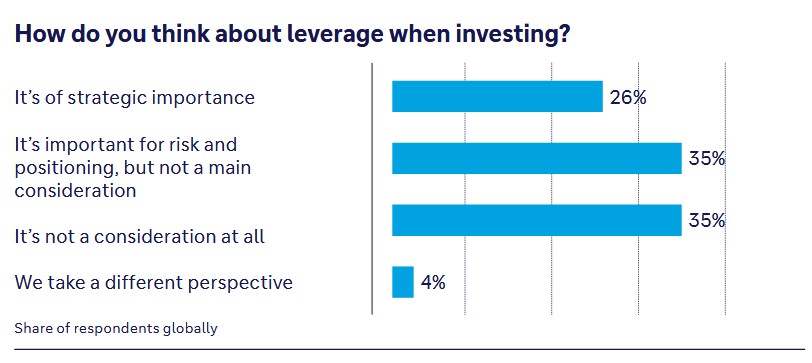

“Family offices around the world regard leverage as an important tool, and they’re using it for a variety of purposes. Sixty-one per cent of those we surveyed said that it was either a strategic topic 'discussed by the investment committee and directly affecting risk and return targets’ or 'an important topic for risk and positioning’,” the report said.

Source: Deutsche Bank

There are regional variations. The report found that Hong Kong-based family offices were most favourable towards leverage, with three-quarters of respondents reporting that it’s either a strategic or important topic. A third of UK-based family offices consider access to leverage very important, taking centre stage in investment decisions, with another 55 per cent saying it’s `good to have, but not vital’. The latter is also true for family offices in the US and Switzerland, where nearly a quarter of respondents also consider it to be very important.

For other family offices, borrowing to invest is less ingrained. In Germany, for example, 51 per cent said leverage was not a consideration when investing, and only a tiny minority there regarded it as a core strategic practice. One in five respondents globally said they did not borrow at all.

Building firepower

On a separate but related theme of “war chests,” the report

said family offices are preparing themselves to rebalance and

manage their leverage when certain asset prices fall. “This also

allows them to seize potential distressed asset opportunities

that may arise, while also enabling them to support their

businesses should other credit lines come under pressure,” it

said.

“Many family offices are committed to holding majority positions in operating companies, listed and unlisted. As trade barriers and inflation have increased globally, they have also often been required to put more liquidity into their corporates,” it said.

Such a finding chimes with anecdotal evidence picked up by this news service, for example, from its recent meeting with bankers and wealth managers in Hong Kong; the disruption to supply chains after Covid and the US “Liberation Day” tariffs, along with other forces such as AI, have prompted many HNW and ultra-HNW business owners to recapitalise their firms. This is proving a significant conversation point for clients and their bankers.

In other findings, the report said that most family offices are engaged in private credit and expect high returns. Most expect returns of 10 per cent or more.

Liquidity

The report examined different attitudes towards liquidity.

The average portfolio managed by survey respondents was 57 per cent illiquid, with most respondents leveraging such assets. Those with more illiquid portfolios tended to do this more often – almost two-thirds of those leveraging illiquid assets had highly illiquid portfolios (75 per cent illiquid or more).

Liquidity levels did vary across regions. In developed markets, the portfolios of those surveyed tended to be more illiquid compared with those in emerging markets – in the UK and Germany, for example, portfolios were 67 per cent and 61 per cent illiquid respectively, while in APAC the equivalent figure was only 39 per cent.

“Family offices generally look at their asset allocation first in terms of liquid versus illiquid assets, and then in corresponding sub-asset classes,” Arjun Nagarkatti, head of the private bank for US & Europe International, said. Although illiquid assets may, by their nature, be difficult to sell quickly, “you have less daily observed price volatility, so you’re not beholden to daily market moves,” he said. “Whether you’re investing in a sports team, an artwork or a stake in a private company, prudent long-term debt can make sense – as long as you’re not too aggressive.”