Client Affairs

FEATURE: India Under Modi, One Year On

On 26 May 2014, Narendra Modi started his tenure as the 15th Prime Minister of India. One year on, this publication takes a look at whether he is living up to the hype.

One year ago, Narendra Modi began his term as India's prime minister. Since he came to power in a landslide electoral victory, with promises of structural reform and rooting out corruption, India has become the emerging market to watch. The nation has been riding a wave of optimism and investors have been quick to get in on the action.

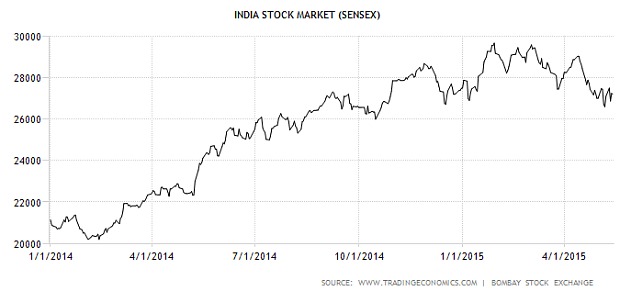

Emerging market funds have been overweighting India and the stock market has certainly given Modi the benefit of any doubt. India's Sensex index climbed 30 per cent over 2014.

Looking at the market rally since Modi’s election, one would assume the Bharatiya Janata Party holds an absolute majority in both the lower and upper house, which isn’t the case. The party has a majority in the lower house but controls only a quarter of the upper house.

And with such optimism about “big bang” reforms come concerns about foundation, something the markets appeared to have deemed unimportant – until recently. Over the last couple of months, the Indian equity market has lost a little steam. Last week, the Sensex index dipped 8 per cent, probably with the realisation that undertaking reform in this country is no easy task and there will be no instant gratification.

“Far from reflecting a weakening of the investment case, we believe this presents an opportunity as, in our assessment, the long-term investment case is undimmed and market expectations for earnings growth at companies had simply risen to levels which were unrealistic in the short term,” said Ajay Argal, head of Indian equities at Baring Asset Management.

So impatient investors have settled down and steadied their expectations with a dose of reality. India has a rigid political system and it’s one that has resisted reform over decades and decades. What’s more, here, you cannot operate on a national level unless you have a good number of local politicians behind you.

“You have to be a supreme bridge-builder,” Dr Marie Owens Thomsen, chief economist at Crédit Agricole Suisse Private Banking tells WealthBriefing.

Although Modi’s popularity is encouraging, the BJP directly controls only eight out of 29 state legislatures. This slows down his plans to improve labour market flexibilities and knock down inter-state fiscal barriers. The unified goods and services tax, which has already been deferred, would create a genuine single consumer market and is seen as a real “game-changer” for an economy that is currently knotted with a flurry of central and state taxes.

The 2015-16 Budget has prioritised spending on infrastructure, an area that has long obstructed the country’s supply-side, and the government has been working hard to encourage state and private sector firms to back efforts to boost infrastructure.

Then there is Modi’s Land Acquisition Bill, which remains stalled in the upper house where his party is in minority. Land acquisition is a contentious issue that has accounted for a third of the government’s stalled projects, meaning there may well need to be some compromises to get it through parliament.

In an attempt to cut red tape and balance the interests of farmers with those of investors, the BJP has proposed to amend the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013. And the rival Congress party has slammed the bill as “anti-farmer”, which in turn has been slammed as a ploy to earn political mileage.

This reform initiative is crucial to the success of Modi’s flagship ‘Make In India’ scheme, which seeks to create more jobs, boost exports and make India a global manufacturing hub.

However, with the Upper House threatening the passage of key bills, Modi’s pledges are not a sure thing. But they are still possible – the Land Acquisition Bill is expected to be passed through a joint session of parliament.

“The government would hold a majority in a combined session of the upper and lower houses, and so could pass a bill by calling such a session,” says Craig Botham, emerging markets economist at Schroders.

“It is not an ideal method, and should be used sparingly to preserve political capital, but will mean the government is able to press ahead with the more important reforms, including land acquisition reform.”

Modi has also been working on reducing poverty levels through an ambitious financial inclusion programme. The Jan Dhan scheme envisages a bank account for every individual.

“This is a bold difference to any previous regime – a real structural positive compared to just handing out money to the poor, which would only lead to unproductive spending,” says Anuja Munde, portfolio manager at Nikko Asset Management.

The fact is things are improving in India. The federal fiscal deficit was reduced to 4.1 per cent of GDP over 2014-15, current budgetary spending fell to below 12 per cent of GDP, while the rupee remained steady against a rising US dollar since October. But it’s not all thanks to Modi.

“There is great temptation in the market that anything positive happening in India is down to Modi – one needs to dampen this enthusiasm a bit and look at the extraneous factors,” says Crédit Agricole’s Thomsen.

Luck too has played its part. The macro environment has been on India’s side. Almost two-thirds of India’s oil is imported so the plunge in global oil prices has drawn in investors looking for “safe haven” oil-importing regions. This has been good news for the country’s trade balance, while bringing down inflation and saving the government money on energy subsidies. Between September 2014 and early 2015, India’s gross monthly oil import bill halved to $7 billion.

“One can be overwhelmed when looking at a list of everything that needs to be done. But governments that do undertake reforms are usually richly rewarded,” said Thomsen.

She uses the United Arab Emirates as an example for reform; the country now ranks almost as high as Switzerland in the World Bank's Ease of Doing Business Index (in 22nd versus 20th place for Switzerland in last year's rankings).

India boasts a young population and a thriving private sector economy. Big changes don’t happen overnight but, going by the past year, there is reasonable hope that the government will, slowly but surely, shake the country out of its archaic shackles. Modi seems to have a good grasp of what needs to be done – and is taking the steps to make it happen.