Investment Strategies

GUEST ARTICLE: Vietnam Is The "New China"

An investment house is beating the drum over the attractions as it sees them of Vietnam's markets - while also conceding some potential risks.

There are a few Vietnam-focused funds nowadays and the country, once associated in many minds with war, civil strife and communism, is on the rise. There has been some discussion around the potential for Vietnam, currently bracketed as a “frontier” market by index organisation Morgan Stanley Capital International, could be elevated to emerging market status, widening the number of investors deemed eligble to hold Vietnam assets. In recent years this publication has been told that Vietnam is one of the more promising of the new economies, helped by youthful demographics and relative low costs. A number of funds and investment houses operate in the space, such as Dragon Capital, Vietnam Holding and PXP Vietnam Asset Management. Another firm with exposure to the country is Eastspring Investments. Ngo The Trieu, chief investment officer, Vietnam, for the firm, talks about the country, its markets and opportunities. The editors of this publication are pleased to share such views and hope they kick off debate; this news service does not necessarily share the opinions of outside contributors. Email tom.burroughes@wealthbriefing.com

There is the high growth rate in labour productivity, the strong expansion of gross domestic product (GDP), and the rising middle class and – remarkable to those who can recall the years of economic isolation and Communist orthodoxy – the enthusiasm for striking free-trade deals.

Above all, and of paramount importance to investors, we have seen enormous growth in the size of the stock market between 2008 and 2017, with high returns achieved on equity.

True, the current space allowed for foreign investment is small. But privatisation and new-share flotations are expected to greatly expand the available room for overseas investors during the coming three years. More on that subject in a moment. First, let’s take a broader look at Vietnam’s extraordinary economic resurgence since the first tentative moves in the late ‘80s towards a more market-driven economy. The formula that proved so successful in other newly-industrialised economies (NIES) has worked its magic in Vietnam. Cumulative foreign direct investment (FDI) has soared since the turn of the Millennium, from about $1 billion to more than $80 billion by 2015

(graph 1). Chart 1: FDI development

In common with other NIES, in Vietnam the great majority of this investment has poured into the manufacturing and processing sector. This in turn has driven a sharp rise in manufacturing production, leading to impressive growth in exports, currently rising at about 10 per cent year-on-year.

Again, as seen in other NIES, Vietnamese manufacturing is moving from an emphasis on labour and resource-intensive activity to more sophisticated production. And the goods thus produced have an ever-greater chance of finding buyers, thanks to Vietnam’s energetic pursuit of trade agreements. Through the 10-nation Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN), Vietnam has comprehensive economic co-operation deals in place with South Korea, China, Japan, India, Australia, New Zealand and, of course, with the other ASEAN nations.

Now, ASEAN has launched negotiations for a free-trade agreement with Hong Kong.

Off its own bat, Vietnam has struck free-trade agreements with South Korea and Chile and an economic partnership agreement with Japan. A free-trade agreement with the customs union of Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan has been signed but has yet to be put into effect. Vietnam has also launched free-trade negotiations with the European Union, the European Free Trade Area and Israel.

But, in the final analysis, Vietnam’s growth momentum is propelled by its greatest single resource: its workforce. More than 70 per cent of Vietnam’s population is under 45 years of age, and it has the second-largest labour force in ASEAN after Indonesia. Indeed, its population ranks 14th in the world in terms of size. Labour costs are low, with monthly wages in manufacturing less than half those being paid in China’s factories. Productivity is currently the lowest in the ASEAN bloc, but the rate of growth of productivity, as measured by annual output per worker in US dollar terms, is the highest.

This youthful demographic profile brings with it a double benefit. The young population will supply both the labour force and the consumers of tomorrow. Nor does this show any sign of changing any time soon – the “population pyramid” for 2020 looks broadly the same as that for 2015 (Graph 1.2).

Chart 2: population pyramid 2020 versus 2015

In terms of the growth of a consumer society, the figures speak for themselves. During the early part of this year, the growth in the volume of retail sales hovered round the 8 per cent mark, while the growth in the value of those sales was about three percentage points higher, indicating buoyancy rather than an inflationary surge. At the same time, consumer confidence reached 112 on the Nielsen index in the fourth quarter of 2016, its joint highest level with a reading taken in early 2015.

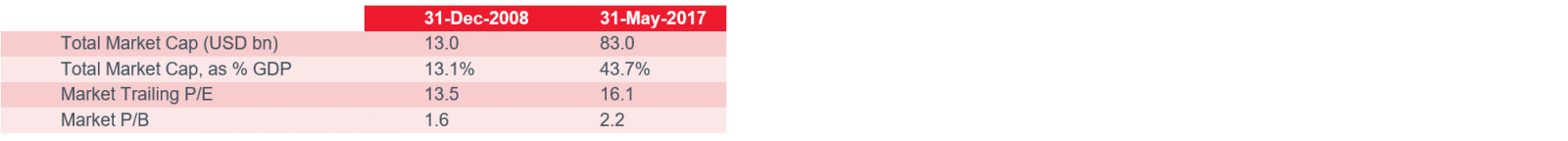

The upshot is that Vietnam is rapidly developing a middle class. The long historical view of the industrial revolution suggests that such a class will, sooner or later, be accompanied by the growth of the equity market. In Vietnam’s case, that view is being borne out. The expansion of the breadth and depth of the country’s stock market is extraordinary. In less than eight and a half years, from December 31 2008 to May 31 2017, total market capitalisation, in US dollar terms, ballooned from $13 billion to $83 billion. Meanwhile, market capitalisation expressed as a percentage of GDP rose from 13.1 per cent to 43.7 per cent (see graph 3).

Graph 3. Market cap and market cap as percentage of GDP

Equally striking has been the growth in daily trading volumes

over that period, from 17.2 million shares to 131 million shares.

Return on equity, at 12.9 per cent, is above that of Thailand, Indonesia and the Philippines. Investor enthusiasm for Vietnamese equities may be damped down by the restrictive effect of laws regulating foreign ownership. Current rules require companies in certain conditional sectors to be subject to relevant foreign ownership limit: 30 per cent in the banking sector; and 49 per cent in the oil & gas and real estate sectors.

Once the stocks already owned by foreign investors are taken into account, the remaining space for foreign investment is just $9 billion, a third of the total “foreign room”.

The good news is that, according to Eastspring Vietnam’s research, this investable universe is set to expand greatly during the next three years, widening the available space for foreign investors from $9 billion to $60.5 billion. Of this $51.5 billion expansion, $32.8 billion is expected when new foreign ownership limit is fully applied by listed companies: $5.8 billion from the newly-floated or privatised state-owned enterprises (SOEs); $8.2 billion from the fresh listing of already floated or privatised SOEs; and $4.6 billion from the new listing of private-sector companies (graph 4).

Graph 4 - Projection of EVN on investable universe of foreigner in next 3 years

Within this expanded universe, 66 per cent of the market capitalisation will be seen in those sectors that will directly benefit from the country’s economic growth: consumer discretionary, industry, information technology, financial services, utilities and materials.

Meanwhile, Vietnam’s bond market is growing rapidly, from issuance of government paper of less than $4 billion in 2011 to more than $12 billion in 2016.

In fairness, there are some downsides when it comes to investing in Vietnam. For example, the World Bank warned in its 2016 report Vietnam 2035, that for the country “to succeed in its growth and economic modernisation ambitions, its cities need to do more to nurture private enterprise and innovation, support the growth of industrial clusters integrated with global value chains, and attract and agglomerate talent”.

The bank also said that “Fulfilling this agenda will require functioning land markets, co-ordinated urban planning, and improved connective infrastructure.” Failings in this last area, said the bank, were hampering Vietnam’s competitiveness in relation to its neighbours by creating logistical inefficiencies.”

These comments were echoed as recently as this month in a report by the International Monetary Fund, which called for “civil service reforms to reduce the public sector wage bill and improvements in public spending efficiency to create room for priority infrastructure and social spending”. Noting another potential downside, it added that “vigilance would be needed to contain rapid credit growth and credit allocation”.

We are confident that Vietnam’s political stability – its last major upheaval is more than 40 years in the past, and strong growth prospects will help overcome the infrastructure issue. In short, for those who were either too young or too late to share in the Chinese success story, Vietnam would seem the obvious investment destination.

Note – This research constitutes an opinion, not factual data