this extra tax revenue,” Dunnett continued.

Some nations within the EU, for example (Luxembourg, Ireland and Malta) set low, single-digit rates. Biden and like-minded politicians want to limit the scope for such “tax competition.” On the other hand, critics argue that tax rates should be a matter for individual countries and their voters. The UK, after all, voted to leave the European Union partly from a desire to put parliament back in charge of tax, instead of “harmonising” rates across national borders.

Corporate taxes, as they ultimately fall on the shoulders of people in various ways (shareholders, employees, etc), have long been criticised because they encourage finagling of different jurisdiction’s tax codes.

Commentators have also argued that tax competition has eroded rates, limiting the ability of governments to raise taxes for their spending plans. On the flipside, defenders of such competition, such as Daniel Mitchell, senior fellow at the think tank, the , argue that this encourages governments to limit taxes beyond what would otherwise be the case. Mitchell has suggested that such efforts to curb different tax rates are tantamount to creating a tax “cartel”.

“Countries with good tax systems will not have any interest in joining Biden’s global tax cartel. Instead, they will maintain their better tax systems and benefit from an increase in jobs and investment as the United States becomes less competitive,” Mitchell wrote in an editorial article on 20 May (Los Angeles Daily News).

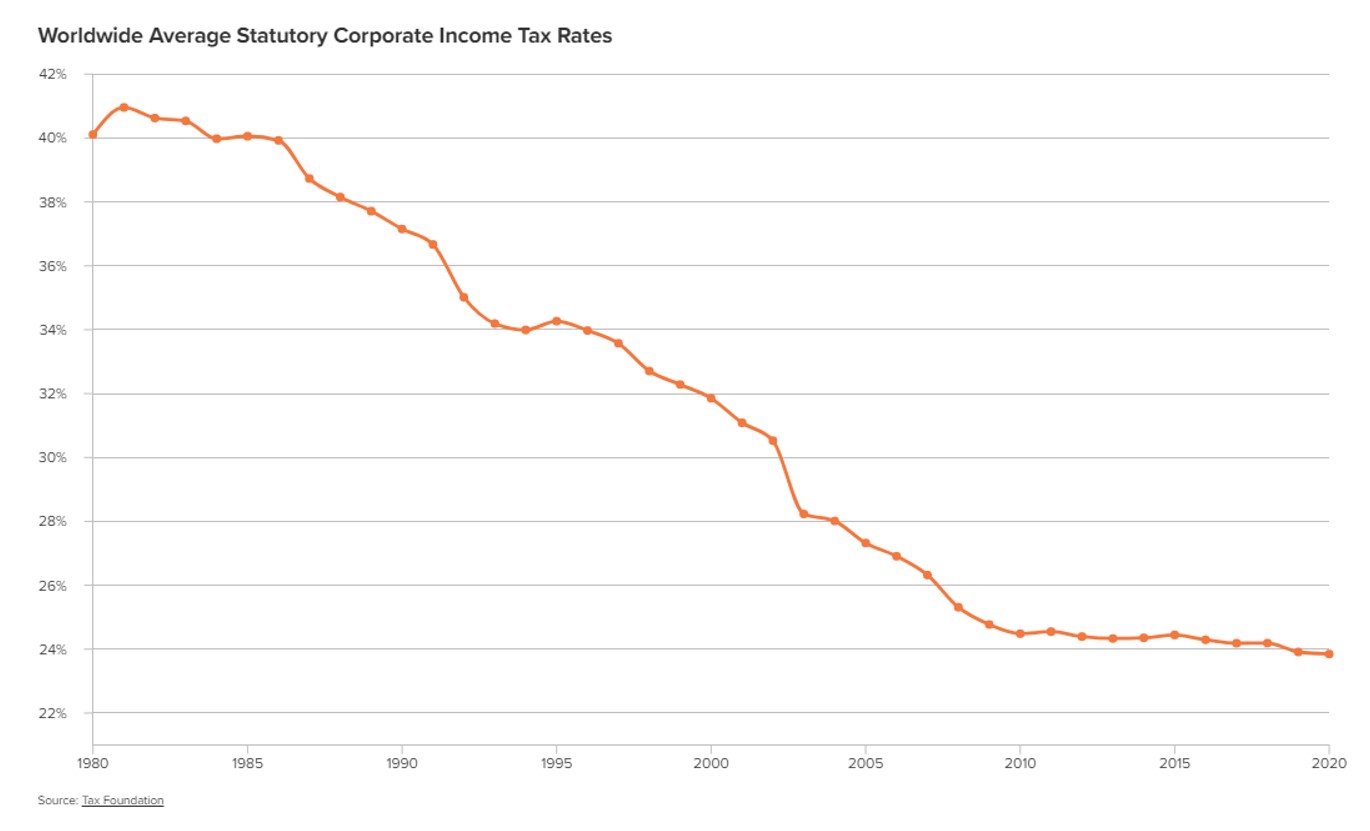

Corporate tax rates have fallen by about half since the early 1980s, as this chart, drawn from the Atlantic Council publication 7 April, 2021), shows. (The chart references figures from the Tax Foundation.)